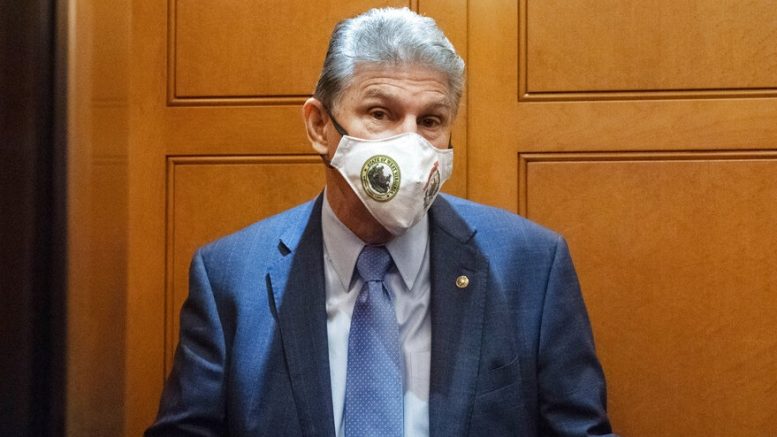

WASHINGTON (AP) — Government reports on rising inflation and the potential costs of President Joe Biden’s social and environment legislation raised fresh questions Friday about the bill’s fate, with both sides hoping the new numbers would influence pivotal Sen. Joe Manchin.

The moderate Manchin, D-W.Va., has spent months forcing Democrats to trim the 10-year, $2 trillion package, arguing it’s too expensive and at times citing growing inflation as a reason to slow work on the bill. On Friday, the Labor Department said consumer prices grew last month at an annual rate of 6.8%, the highest in 39 years.

A separate report from the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office said that if many of the bill’s temporary spending boosts and tax cuts were made permanent, it would add $3 trillion to the price tag. That would more than double its 10-year cost to around $5 trillion. Democrats called the projections from the Republican-requested report fictitious.

Manchin aides did not respond to requests for comment. Manchin said in a brief interview Thursday that he wanted to know “where we are in inflation and where we are on the true price” of the bill, adding he was “very concerned.”

The latest inflation figures prompted Biden to use some of his strongest language yet, telling reporters at the White House on Friday, “I think this is the peak of the crisis.” While the numbers illustrate a clear political danger for the administration, the recent performance of financial markets suggests investors don’t see inflation as a long-term problem.

Friday’s reports popped out two weeks before Christmas, by when Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., hopes to end months of talks among Democrats and finally push a compromise bill through the Senate. The House approved an initial version last month.

With Manchin still seeking cuts in a measure that originally cost $3.5 trillion, the day’s reports at the least increased his leverage in a tortuous process that’s already seen several near-death moments caused by Democratic infighting. At worst, the numbers fueled worries that Manchin might abandon the package, sinking it.

“I don’t know the answer to that,” Biden said at the White House when asked if he could win Manchin’s support. He said he’d talk to the lawmaker early next week.

Every Democrat in the 50-50 chamber will have to back the bill so Vice President Kamala Harris can cast a tie-breaking vote to approve it.

The political sensitivity of inflation and its impact on the Democratic bill, a collection of family services, health care and climate change priorities, was illustrated as leaders of both parties tried to spin the numbers to their advantage.

Democrats argued that the inflation report intensified the need to approve the measure. They said the legislation’s spending and tax credits for health care, children’s costs, education and other programs would help families cope with rising prices. Most of the bill is paid for with tax boosts on the wealthy and big corporations.

The legislation’s impact will be “reducing costs for ordinary people,” Biden said.

Republicans said the legislation’s expenditures would further feed inflation, which has been driven by supply chain delays making products less available and spending prompted by a strong underlying economy.

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., said inflation means “the average American has gotten a pay cut,” adding, “It is unthinkable that Senate Democrats would try to respond to this inflation report by ramming through another massive socialist spending package in a matter of days.”

Possibly mitigating the political impact of Friday’s inflation numbers was that they were expected and represented a modest rise from October’s 6.2%.

Adding any additional juice to the economy might worsen inflation. But the extra fiscal stimulus over the next several years in Democrats’ bill would be less than 1% the size of the entire U.S. economy, making its likely inflationary impact mild, said the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

Democrats limited the duration of many initiatives in their package to help contain the bill’s price tag. That includes extending enhancements to the child tax credit for just one year and free, universal pre-school for only six years.

It’s an accounting move both parties have used to make their budget plans seem more affordable — even though they would like their proposals to be permanent and some may be extended because they are popular. Republicans used such phaseouts robustly for their big tax cuts in 2001 and 2017.

“If you believe these programs go away after one, two or three years, you shouldn’t have a driver’s license,” said Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, top Republican on the Senate Budget Committee, who requested the CBO estimates. He said the bill’s higher price tag and rising inflation meant Democrats’ legislation would be “lethal to the economy and lethal to your paycheck.”

Democrats argued the estimated added $3 trillion cost was bogus because if they decided to seek any future extensions of their initiatives, they would propose savings to pay for them.

As if sharing a script, Psaki called the GOP claims “fundamentally dishonest” and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., said Republicans were using “fake scores based on mistruths.” House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., called the numbers “a phony score of an imaginary bill.”

Outside groups have produced similar estimates about the legislation’s cost if its programs were permanent. CBO numbers usually have more clout in Congress because the agency’s impartiality is respected.

Much about the legislation remains in play. Manchin still wants to remove a paid family leave program and curb or eliminate some tax breaks aimed at encouraging a shift to cleaner energy. Moderate Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., has also pushed to trim the measure.

Democrats have also had differences over how to ease limits on federal tax deductions that people can take on state and local taxes. In addition, the Senate parliamentarian must decide whether some provisions — including a top party priority of letting millions of migrants remain in the U.S. — violate the chamber’s rules and should be removed.

That’s left it unclear whether Schumer will be able to meet his Christmas deadline.