The Associated Press

As governors loosen long-lasting coronavirus restrictions, state lawmakers across the U.S. are taking actions to significantly limit the power they could wield in future emergencies.

The legislative measures are aimed not simply at undoing mask mandates and capacity limits that have been common during the pandemic. Many proposals seek to fundamentally shift power away from governors and toward lawmakers the next time there is a virus outbreak, terrorist attack or natural disaster.

“The COVID pandemic has been an impetus for a re-examination of balancing of legislative power with executive powers,” said Pam Greenberg, a policy researcher at the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Lawmakers in 45 states have proposed more than 300 measures this year related to legislative oversight of executive actions during the COVID-19 pandemic or other emergencies, according to the NCSL.

About half those states are considering significant changes, such as tighter limits on how long governors’ emergency orders can last without legislative approval, according to the American Legislative Exchange Council, an association of conservative lawmakers and businesses. It wrote a model “Emergency Power Limitation Act” for lawmakers to follow.

Though the pushback is coming primarily from Republican lawmakers, it is not entirely partisan.

Republican lawmakers have sought to limit the power of Democratic governors in states such as Kansas, Kentucky and North Carolina. But they also have sought to rein in fellow Republican governors in such states as Arkansas, Idaho, Indiana and Ohio. Some Democratic lawmakers also have pushed back against governors of their own party, most notably limiting the ability of embattled New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo to issue new mandates.

When the pandemic hit a year ago, many governors and their top health officials temporarily ordered residents to remain home, limited public gatherings, prohibited in-person schooling and shut down dine-in restaurants, gyms and other businesses. Many governors have been repealing or relaxing restrictions after cases declined from a winter peak and as more people get vaccinated.

But the potential remains in many states for governors to again tighten restrictions if new variants of the coronavirus lead to another surge in cases.

Governors have been acting under the authority of emergency response laws that in some states date back decades and weren’t crafted with an indefinite health crisis in mind.

“A previous legislature back in the ’60s, fearing a nuclear holocaust, granted tremendous powers” to the governor, said Idaho state Rep. Jason Monks, a Republican and the chamber’s assistant majority leader.

“This was the first time I think that those laws were really stress-tested,” he said.

Like many governors, Idaho Gov. Brad Little has repeatedly extended his monthlong emergency order since originally issuing it last spring. A pair of bills nearing final approval would prohibit him from declaring an emergency for more than 60 days without legislative approval. The Republican governor also would be barred from suspending constitutional rights, restricting the ability of people to work, or altering state laws like he did by suspending in-person voting and holding a mail-only primary election last year.

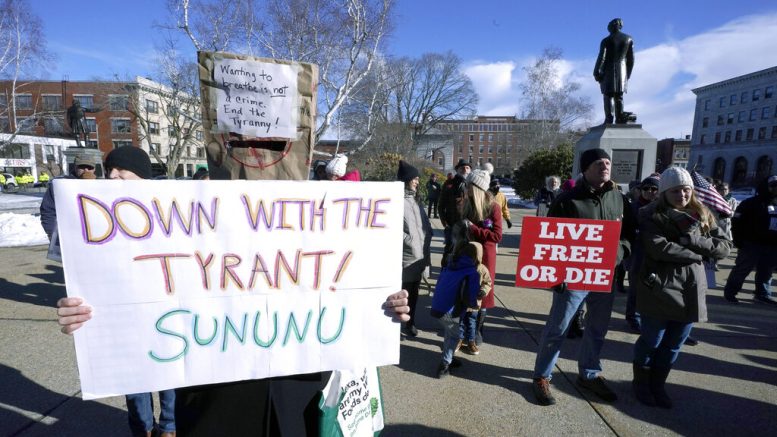

A measure that recently passed New Hampshire’s Republican-led House also would prohibit governors from indefinitely renewing emergency declarations, as GOP Gov. Chris Sununu has done every 21 days for the past year. It would halt emergency orders after 30 days unless renewed by lawmakers.

Next month, Pennsylvania voters will decide a pair of constitutional amendments to limit disaster emergency declarations to three weeks, rather than three months, and require legislative approval to extend them. The Republican-led Legislature placed the measures on the ballot after repeatedly failing to reverse the policies Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf implemented to try to contain the pandemic.

In Indiana, the Republican-led Legislature and GOP governor are embroiled in a power struggle over executive powers.

The Legislature approved a bill this past week that would give lawmakers greater authority to intervene in gubernatorially declared emergencies by calling themselves into special session. The House Republican leader said the bill was not “anti-governor” but a response to a generational crisis.

Gov. Eric Holcomb, who has issued more than 60 executive orders during the pandemic, vetoed the bill Friday. He contends the legislature’s attempt to expand its power could violate the state Constitution. Legislative leaders said they intend to override the veto, potentially setting up a legal clash between the legislative and executive branches. Unlike Congress and most states, Indiana lawmakers can override a veto with a simple majority of both houses.

Several other governors also have vetoed bills limiting their emergency authority or increasing legislative powers.

In Michigan, where new variants are fueling a rise in COVID-19 cases, Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer vetoed GOP-backed legislation last month that would have ended state health department orders after 28 days unless lengthened by lawmakers.

Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine, a Republican, contended that legislation allowing lawmakers to rescind his public health orders “jeopardizes the safety of every Ohioan.” But the Republican-led Legislature overrode his veto the next day.

“It’s time for us to stand up for the legislative branch,” sponsoring Sen. Rob McColley told his colleagues.

Kentucky’s GOP-led Legislature overrode Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear’s vetoes of bills limiting his emergency powers, but a judge temporarily blocked the laws from taking effect. The judge said they are “likely to undermine, or even cripple, the effectiveness of public health measures.”

In some states, governors have worked with lawmakers to pare back executive powers.

Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson, a Republican, signed a law last month giving the GOP-led Legislature greater say in determining whether to end his emergency orders. It was quickly put to the test by the Arkansas Legislative Council, which decided to let Hutchinson extend his emergency declaration another two months.

Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly, a Democrat, also enacted a law last month giving legislative leaders power to revoke her emergency orders. Top Republican lawmakers immediately used it to scuttle a Kelly order meant to encourage counties to keep mask mandates in place.

“The power of the executive has been emasculated when it comes to the Emergency Management Act,” Democratic state Rep. John Carmichael said. “That may have very dire consequences in other circumstances and other disasters.”

Kelly said it will be harder to persuade people to keep wearing masks without state or local mandates. She said her orders had relieved pressure on local leaders and businesses.

“Let me be the bad guy. Let me be the one who mandates so that they don’t have to make those kinds of decisions,” Kelly said.

Republican lawmakers insisted that their push to curb the governor’s power is not partisan. Lawmakers said they didn’t understand how broad the governor’s power was until she started issuing orders last spring to close K-12 schools, limit indoor worship services and regulate how businesses could reopen.

House Speaker Pro Tem Blaine Finch said he believes the changes in Kansas’ emergency management law will encourage future governors to “use that power sparingly” and collaborate with lawmakers.

“Our system is set up not to give one person of any party too much power over the lives of Kansans,” he said. “We’re supposed to have checks and balances.”