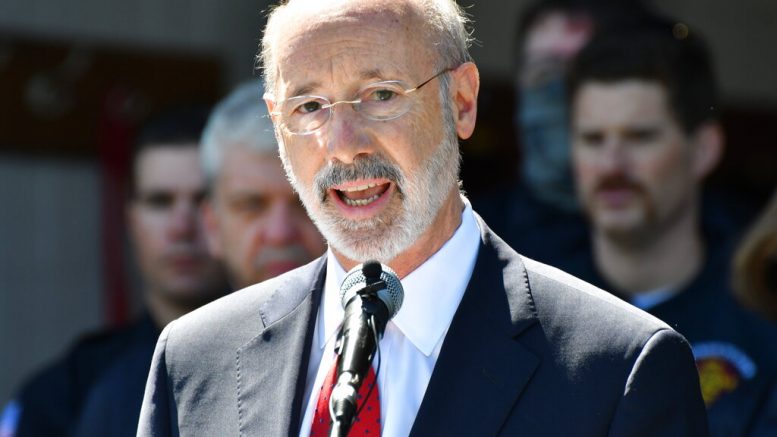

HARRISBURG (AP) — With just a year and a half left in office, Gov. Tom Wolf’s primary focus will be convincing the Republican-controlled Legislature to modernize how state aid is distributed to Pennsylvania’s public schools — a shift that could carry a price tag of $1 billion.

Doing so would direct more money to Pennsylvania’s poorest school districts — including districts with the state’s biggest proportions of Black students — as well as to growing suburban districts whose share of state aid reflects early 1990s demographics or political compromises in the Legislature.

In an interview Thursday with The Associated Press, the Democratic governor also said he remains dedicated to two initiatives opposed by many Republicans: adding tolls to nine major interstate bridges in need of upgrades and forcing fossil fuel-fired power plants to pay a price for the carbon dioxide they emit.

On the proposed bridge tolls, Wolf said he hasn’t seen a better idea to fill the growing highway construction-funding gap worsened by stagnating gasoline tax revenues.

On the other, the centerpiece of his agenda to fight climate change, Pennsylvania’s coal-fired power plants have been closing anyway, Wolf said, and his plan at least promises aid to coal communities that lose plants in the future.

Wolf, 72, is term-limited and must leave office in January 2023.

He took office in 2015, right as the federal government released a report showing that Pennsylvania had the nation’s starkest spending gap between rich and poor school districts.

Soon after, lawmakers approved a modernized school-funding distribution formula, but Wolf had two challenges: boosting state aid and getting lawmakers to push more of the money through the new distribution formula.

Wolf said he was close in June to getting lawmakers to route all school aid through the new formula, a step that requires $1.1 billion to avoid reductions in other districts’ shares.

Instead, lawmakers approved $300 million — no small amount, but far short of the required funds. One key reason Wolf thinks he might still secure that funding next year is the state’s flush coffers, thanks to heaps of federal coronavirus aid.

“The state has never been, I don’t think, at least in my lifetime that I know, in as good a financial shape,” Wolf told the AP. “So that’s another thing that makes this possible. We can look at doing this kind of thing, even looking at a $1.1 billion expenditure. In our current financial situation, we can afford to do that.”

To some extent, Wolf has had success in securing new education funding. He boosted education aid over seven budgets by roughly $2 billion a year, the goal he had initially set out for his first term.

Wolf has also played a lot of defense. He has vetoed 51 bills, putting him on track to compile the most vetoes by any governor since Milton Shapp in the 1970s. Enough Democratic lawmakers stuck by Wolf to turn back every Republican override attempt.

One bill Wolf just vetoed — a Republican plan to overhaul state election law — he called “voter suppression,” although there may yet be more negotiations on election legislation in the fall, particularly with counties pressing for improvements to the state’s expansive mail-in voting law Wolf signed in 2019.

Republicans, with solid House and Senate majorities throughout Wolf’s term in office, show no sign that they will yield to some of Wolf’s highest-profile priorities: multi-billion-dollar tax increases, a tax on Pennsylvania’s huge natural gas industry and an increase in the state’s rock-bottom minimum wage, among them.

Where possible, Wolf has pursued policy through executive action to get around the Legislature.

That includes his greenhouse-gas initiative and his Department of Transportation’s plan to toll major interstate bridges.

Republicans have suggested that Wolf might be willing to drop one or the other in exchange for concessions on election legislation or school funding.

But Wolf said Thursday he has no intention of doing so.

Some Republicans have backed a plan to borrow the money to pay for the bridges, but Wolf’s administration has rejected the idea, saying it doesn’t solve the problem.

Wolf’s greenhouse-gas initiative has seen the stiffest resistance from coal country lawmakers, who say merely discussing it is accelerating the possibility that utilities will shut down the coal-fired power plants in their districts.

Wolf said those communities will be better off under his plan getting some of the hundreds of millions of dollars in fees on carbon dioxide emissions than nothing when the plant shuts down anyway.

“I think it’s high time that we stop saying, ‘Let’s not do anything, let’s just pretend this isn’t going to happen, let’s not give you anything,'” Wolf said. “Let’s actually give you some compensation for the disruption this is causing, for whatever reason.”